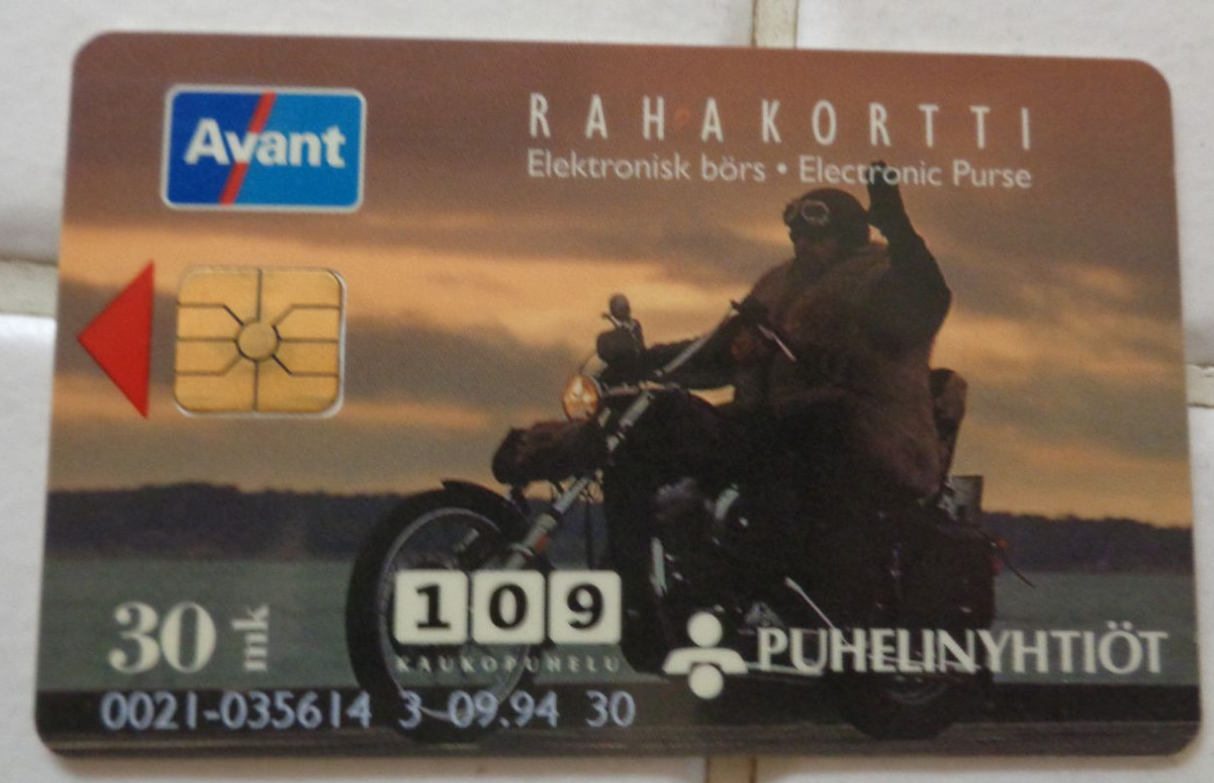

In reflection, the introduction of the Avant Card from Finland failed to register any discernible impact on seigniorage income. This outcome can be attributed to the central bank’s hands-off approach to the system for a period exceeding three years, coupled with consistently low transaction volumes during that timeframe.

The deliberation over the legal tender status for e-money was a meticulous process conducted in anticipation of the Avant system’s launch. Two pivotal perspectives were scrutinized: firstly, from the vantage point of the central bank’s monopoly in currency issuance, and secondly, considering the potential obligation for merchants to accept e-money as a valid form of payment.

Analysis revealed that neither standpoint lent credence to the notion that e-money could attain the same status as traditional coins and banknotes. Despite possessing certain cash-like attributes, e-money bore closer resemblance to bank deposits. Consequently, its issuance could not be deemed a monopoly exclusive to the central bank.

Equally crucial was the realization that mandating merchants or other creditors to accept e-money as payment would be an impractical imposition. Such a mandate would force these entities to make substantial investments in new and potentially costly equipment. Thus, the logical and pragmatic conclusion emerged: central bank e-money would not be granted legal tender status.

In navigating the intricate landscape of financial policy and technological evolution, the Avant Card saga underscores the delicate balance between innovation and adherence to established monetary principles. As we delve into the implications of non-traditional currency forms, the Avant experiment serves as a case study in the nuanced interplay between legal considerations and the practical realities faced by businesses and individuals alike.